Staking and Reward Mechanisms in Proof of Stake Protocols#

Innovation & Ideation

Key Insights

There are various applications of PoS-based Systems evolving using diverse reward mechanisms.

Reward mechanism is a critical aspect, affecting both incentive structures and system decentralisation.

There is a trade-off: the more open the staking process is, the more inequality the reward distribution tends to be.

The way how PoS is implemented greatly matters in its equality and decentralisation.

We need to critically think about various PoS protocols. Not only know the high return rate, but also realise the centralisation and risks in different systems.

Introduction#

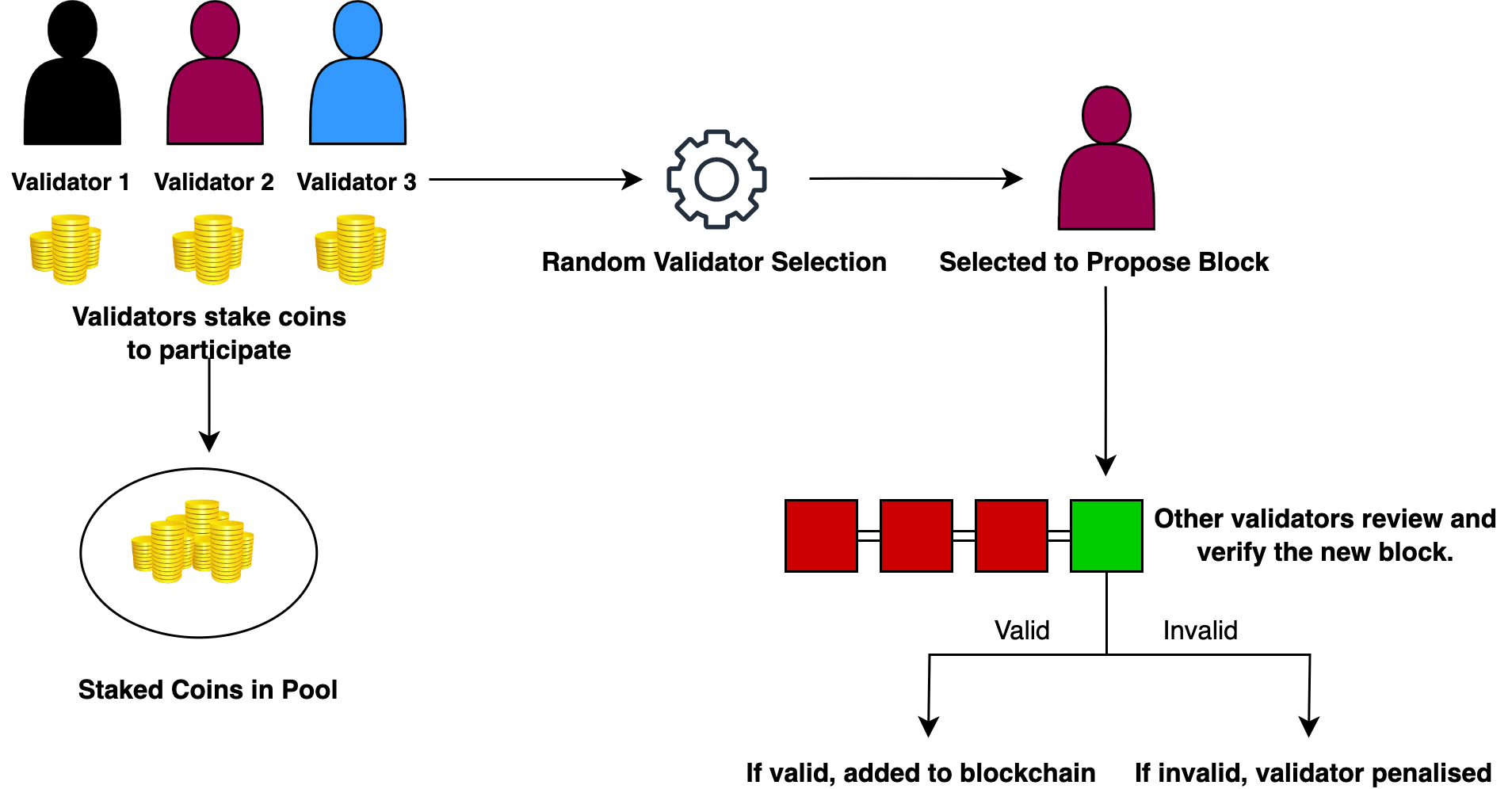

Blockchain’s trustless foundation removes the necessity for inter-party trust, with its security and decentralisation hinging on a fair consensus mechanism while Proof-of-Work (PoW) and Proof-of-Stake (PoS) are currently the two most used consensus protocols. Proof-of-Work (PoW) involves computating power competition and thus is criticised for its environmental footprint and potential inequities in mining. Conversely, Proof-of-Stake (PoS) operates on asset collateralisation i.e., tokens and is getting popular due to its energy efficiency but faces risks of wealth concentration. This science note summarises Dr. Sheng-Nan Li’s talk, which delves into the nuances and challenges of PoS protocols, especially focusing on staking and reward mechanisms [Li23].

Fig. 12 Proof-of-Stake (PoS) Consensus Mechanism.#

Overview of PoS Reward Mechanisms#

To discuss the properties of staking and reward distribution in PoS, Ethereum 2.0, Cardano, and Polkadot are selected as examples.

Ethereum 2.0#

Ethereum 2.0 [ethereumorg23], launched on September 15, 2022, signifies a major shift in the blockchain realm by adopting the Proof of Stake consensus protocol, specifically the Casper-FFG and LMD-GHOST versions. Central to this new protocol are validators as the main actors, including attesting to blocks and proposing new ones. The attestation process involves a minimum of 128 validators who propose attestations or votes as the attesting committee, from which 16 are chosen as Aggregators. Additionally, one validator is designated as the block proposer to propose one block per slot. The reward with a sum_weight of 64 is structured based on various criteria as:

timely vote for the correct source checkpoint (weight=14)

timely vote for the correct source checkpoint (26)

timely vote for the correct head block (14)

participated in a sync committee: (2)

proposed a block in the correct slot: (8) ( ~ 7/8 attesting reward )

Additionally, a key concept of the consensus and staking aspect is the validator effective balance, which is capped at 32 ETH and triggers ejection when it reaches 16 ETH. It takes 12 seconds for a slot and around 6.5 minutes for an Epoch (32 slots). Reward payout happens after two epochs following the finalisation of a block. For the reward distribution, we have:

On the other hand, penalties are in place for cases such as failing to vote timely on the correct head, source, or target. However, there is no penalty for failing to propose a block. The more severe penalty, known as slashing, applies to proposers who propose two different blocks for the same slot and to attesters who engage in ‘surround voting’ or ‘double voting.’ This results in a 36-day removal and the burning of a fraction of the staked ether.

Cardano#

Cardano, with its Shelley update [car23] introduced on July 29, 2020, employs the Ouroboros Praos consensus protocol (PoS). Central to its system are stake pools consisting of stake pool operators (SPOs), who act as slot leaders responsible for producing blocks. Additionally, there are delegators who can allocate their stakes to these pools. Cardano’s system divides time into epochs, with each epoch containing 432,000 slots (1 second) that equate to five days. Rewards are dispensed at the end of each epoch. Cardano introduces a unique staking system with its “Pledging” or self-staking mechanism, allowing stake pool operators to commit their own ADA cryptocurrency, influencing the rewards they can potentially earn. To ensure the network remains decentralised and no single pool gains excessive control, Cardano has implemented a “Saturation Parameter.” This parameter sets an optimal size for each pool, beyond which rewards begin to diminish, encouraging a balanced distribution of stakes across various pools. Additionally, the total rewards, sourced from a maximum supply, are influenced by factors like the pool’s performance, and they are distributed proportionally based on produced blocks and the pool’s total active stake. After deducting declared fees for pool operation, the remaining rewards are shared proportionally among all delegators, including the pool operator.

Polkadot#

Launched in May 2020, Polkadot operates using a Nominated Proof of Stake (NPoS) consensus mechanism [Das23]. In this system, nominators can select up to 16 validator candidates, with the active validator set capped at 297. These validators, once elected, are responsible for producing blocks in the relay chain and also accept proofs from collators, who collect transaction data and proofs from the parachains. Time is organised into eras, each lasting 24 hours, during which validators produce blocks. Reward payout happens at the end of every era, with the total rewards following an inflationary model, estimated at approximately 10% yearly by total stake. Validators earn era points for their contributions, which influence their rewards but are separate from their stakes. Notably, the rewards are generally equal among all validators but can vary based on the era points they’ve accumulated. Validators can also claim a commission fee, while nominators share the rewards among the top 256 nominators, proportionally to their stake. However, there are slashing mechanisms in place including penalties of a fixed percentage of the stake of validator slot ranging from 0.1% to 100% and kicking out range from removing from the list of candidates in the next election to removing from all the nominators’ lists of trusted candidates, depending on the severity of the violation.

Overall, PoS protocols of Ethereum 2.0, Cardano, and Polkadot differ in the terminologies, the main actors and their roles, the incentive and reward distribution, and other technical details. This leads to the next question whether the rewards are fairly distributed to the validators in real PoS-Platforms.

Coin |

Launch |

Roles |

Reward period |

Slashing |

Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ethereum 2.0 (PoS) |

Sep-22 |

Proposer/ Attesting committee |

Epoch (~6.5mins) |

YES |

capped at 32 ETH |

Cardano (PoS) |

Jul-20 |

Pool operator/ delegator |

Epoch (5 days) |

NO |

Pledge factor/ saturation |

Polkadot (NPoS) |

May-20 |

Validator/ Nominator/ Collator |

Era (24 hours) |

YES |

Era points/ equally distribute |

Decentralisation of Reward Distribution#

To evaluate the decentralisation of reward distribution, particularly the distribution of wealth among participants, two primary metrics are employed:

Gini Index#

The Gini Index [Has23] is the most frequently used inequality index of income or wealth distribution among a nation’s population. It can theoretically range from 0 (complete equality) to 1 (complete inequality, where one participant possesses everything while others have nothing). In PoW-based systems, the Gini Index measures the inequality of mining revenue distribution among miners. The Gini Index is applied to the stakes and rewards of validators as:

Nakamoto Coefficient#

The Nakamoto Coefficient [Boa23] quantifies decentralisation by specifying the number of participants needed to compromise the system. In this setting, it is based on the stakes of validators. It specifies the minimum share of participants required to hold more than 50% of the staking power. A higher Nakamoto Coefficient indicates better decentralisation of the protocol. It’s expressed as:

Diving deeper into the landscape, Polkadot and Cardano present contrasting approaches. Despite its limited set of validators, Polkadot has seen substantial growth in stake pools. On the other hand, with an unlimited validator set, Cardano recently noted that only around 40% of its pools receive rewards in each epoch. When analysing the distribution patterns, Polkadot emerges as a leading player in both stake and reward distribution. Its design, which emphasises equal reward distribution, has resulted in the lowest Gini Index and the most substantial Nakamoto Coefficient. In contrast, Cardano, despite its open validator set, exhibits a relatively high level of inequality.

In essence, how PoS is implemented plays a crucial role in determining both its equality and decentralisation [HTC+21].

General Framework of PoS Modeling#

To clarify components that characterise the staking and reward of PoS protocols and develop an evaluation framework for better protocol design, an extensible framework of modelling (D)PoSs is introduced by Dr. Li. The framework process is split into three parts:

Planning the total reward before the reward period;

Designing the staking behaviours and the reward distribution during the reward period;

Measurement after prolonged operation.

Use-case: Staking Model in Hedera#

Hedera Hashgraph, with its unique consensus mechanism known as the hashgraph consensus algorithm, offers an interesting case study for staking models. The hashgraph consensus algorithm operates using a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). The hashgraph methodology facilitates transaction processing at speeds vastly superior to conventional proof-of-work blockchains.

A negative value of its Degree Assortativity for weekly transaction networks suggests a disassortative nature, indicating that a significant portion of the participants likely transact through a select few dominant intermediaries. When examining wealth distribution within the network, it is observed that early users, those who joined during the initial month or year, tend to hold a substantial amount of tokens. However, a shift towards a more equitable distribution is evident post mid-2022.

The dynamics of account growth, the rate of Daily Active Accounts (DAA), and the volume of daily transaction fees are used in empirical data analytics.

Firstly, the growth of daily transaction fees is fitted and forecasted by the log-log function for better planning of the future total reward. Assuming the reward solely comes from transaction fees without inflation or self-finance, the yearly total reward can be scheduled in different trends such as increasing, decreasing, and constant trends.

Secondly, regarding the modelling of staking behaviours such as staking selection, stakers base their decisions on the time-weighted values of a validator’s performance. This is used when they select a node to determine the percentage of each staker’s balance. This encompasses factors like historical participation levels and reward rates. As for saturation, the historical reward rate is diluted when received stakes exceed a specified maximum cap and plummets to zero when the received stake is below a minimum threshold. Otherwise, the reward rate remains at 1. As for validator performance and staker preference, two memory functions which assign weight to the node’s participation level and reward rate in each reward period, that is the probability that delegators select validators based on their participation and reward rate, are combined to produce a score for each node.

Thirdly, the daily total reward is distributed among nodes and stakers. Each node’s daily reward is determined by its latest participation level relative to a specified threshold and the proportion of stakes received by the node. Similarly, each staker’s daily reward depends on the participation level of their selected node and their share of the stake in that node’s total received stakes.

Finally, the evaluation of decentralisation using the Gini Index suggests rewards are more equitably distributed among validators (nodes) than stakers. Moreover, the Nakamoto Coefficient indicates that a voting-weighted system is more decentralised than the “one stake one vote” approach.

Conclusion#

Modelling (D)PoS offers insights into the long-term implications of protocol adjustments and enhances our understanding of the behavioural tendencies of validators or stakers. It also highlights their influence on system decentralisation. As we delve deeper into various PoS protocols, it’s crucial to recognise not just the attractive return rates but also the centralisation and potential risks inherent in different systems.

References#

- Boa23

Cryptoken Board. Nakamoto coefficient — how decentralized is your blockchain. medium, 2023. URL: https://medium.com/@cryptoken_board/nakamoto-coefficient-how-decentralized-is-your-blockchain-04842c03ed48#:~:text=On%20a%20typical%20Proof%20of,all%20stake%20on%20the%20network.

- car23

cardano. Cardano roadmap - shelley. Cardano, 2023. URL: https://roadmap.cardano.org/en/shelley/.

- Das23

Lipsa Das. What is nominated proof of stake (npos)? Ledger Academy, 2023. URL: https://www.ledger.com/academy/topics/blockchain/what-is-nominated-proof-of-stake-npos#:~:text=NPoS%20allows%20nominators%20to%20choose,choose%20up%20to%2016%20validators.

- ethereumorg23

ethereum.org. Proof-of-stake (pos). ethereum.org, 2023. URL: https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/consensus-mechanisms/pos/.

- Has23

Joe Hasell. Measuring inequality: what is the gini coefficient? ourworldindata, 2023. URL: https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-the-gini-coefficient.

- HTC+21

Yuming Huang, Jing Tang, Qianhao Cong, Andrew Lim, and Jianliang Xu. Do the rich get richer? fairness analysis for blockchain incentives. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Management of Data, 790–803. 2021.

- Li23

Shengnan Li. Effects of consensus and incentives on the functioning of blockchains. University of Zurich, 2023.