Exploring the World of Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) in Blockchain#

Academic insight

Key Insights

MEV’s impact extends beyond transaction ordering profits, influencing network congestion and fee inflation, with miners potentially altering their behaviour to chase these extractable values.

To reduce the manipulative impact of MEV on transaction order, proposals for including transactions based on objective metrics like gas prices or timestamps are being examined.

The emergence of specialised roles, including arbitrage traders and bot operators, signifies the development of a sophisticated MEV ecosystem, focusing on the optimisation of transaction placement for maximum returns.

To enhance the fairness of blockchain networks, new protocols are being developed that aim to level the playing field by minimising the advantages of MEV for miners with greater computational resources.

To protect end users from predatory MEV strategies, such as sandwich attacks, solutions are being researched that would obscure transaction details from potential attackers.

To maintain the integrity of consensus mechanisms in the face of MEV, strategies are being considered that could deter miners from deviating from honest practices for short-term gains.

Introduction#

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) also known as Miner Extractable Value (MEV), an increasingly crucial topic in the realm of blockchain research, refers to the monetary advantage a miner can acquire by strategically manipulating transactions in a block they produce. Recent studies have begun to shed light on the complexities of MEV, exposing both its potential threats and opportunities within the blockchain infrastructure. This science note offers an in-depth analysis of recent academic findings, focusing on the operational dynamics of MEV, its implications on the fairness and security of blockchain networks, and the proposed solutions to mitigate its effects.

Deconstructing MEV#

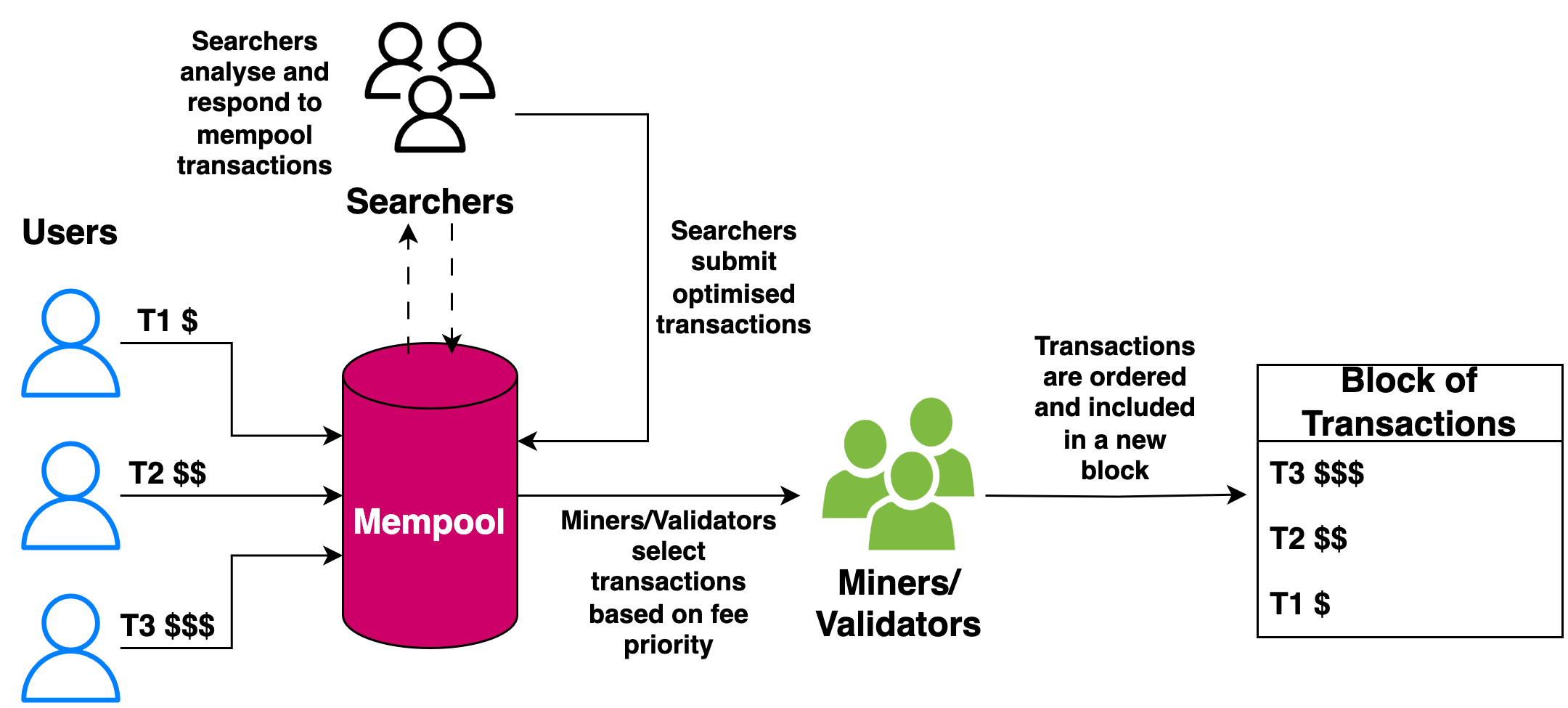

Fig. 8 Transaction Prioritisation in the Context of Miner Extractable Value (MEV).#

The concept of Miner/Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) was coined by Daian et al. [DGK+20] to define the maximum profit a miner can secure by strategically adjusting transaction sequences. This practice, prevalent in various financial applications, has evolved into a profitable industry dominated by specialised searchers like arbitrage traders and bot operators. These searchers focus on identifying opportunities and constructing transactions to maximise MEV, often involving the precise placement of transactions.

In blockchains supporting smart contracts, miners or validators prioritize transactions with higher fees for inclusion in blocks, impacting the mempool where unconfirmed transactions wait, often delaying those with lower fees. A common MEV scenario involves miners exploiting arbitrage opportunities on trading platforms, sometimes leading to bidding wars with bots for higher transaction fees [Cha22].

The impact of MEV is significant, particularly on end users who pay transaction fees, and on miners who select transactions based on these fees to maximise profits. While MEV is a relatively new field, it has already seen substantial research focused on understanding, quantifying, and mitigating its effects, especially in terms of common sources of MEV and the security concerns they pose. Common strategies include front running, where transaction fees are exchanged for block space with non-miner MEV extractors, and back running, which involves manipulating transactions for profit from on-chain events [Cha22].

Frontrunning: This involves placing the attacker’s transactions ahead of the victim’s. For instance, an attacker may offer higher transaction fees to ensure their transaction gets executed first to exploit a rare market opportunity. Block space is sold to non-miner MEV extractors in return for transaction fees through Priority Gas Auctions.

Backrunning: In this scenario, the attacker places their transaction right after the victim’s transaction to take advantage of the market change initiated by the victim. For instance, if a transaction on Exchange X significantly increases an asset’s price, it opens an arbitrage opportunity. Here, the backrunner could purchase the same asset from another exchange, X’, at a lower cost and then sell it on X, keeping the price difference [YZH+22]. In this scenario, the backrunner’s transaction does not harm the user and aids in maintaining price consistency between the two exchanges. In a similar context, backrunning can also be used to capitalise on Oracle updates for liquidation opportunities [QZG+21].

Sandwich Attacks: Sandwich attacks present a more complex MEV extraction method where the attacker places two transactions, one before and one after the victim’s regular trade. The goal is to manipulate asset prices in such a way that the attacker benefits from the victim’s loss [ZQT+21]. However, executing sandwich attacks can be risky for the attacker as any deviation from the desired transaction order can lead to financial loss. In most cases, these attacks are executed via MEV auction platforms.

Bribery Attacks: Attackers may generate MEV to encourage miners to act in their favour, this is known as a bribery attack. These attacks can range from incentivizing miners to temporarily delaying a transaction by offering higher fees for a conflicting transaction to more complex schemes facilitated by smart contracts [TYME21] [WHF19]. The impact of bribery attacks varies depending on the specific application.

Impact on Blockchain Fairness and Security Risks#

Eskandari et al. [EMC20] highlighted a disconcerting aspect of economic inequality that MEV introduces into a system fundamentally designed for decentralisation and equality. Their research showed that miners with more significant computational resources are advantaged, leading to an unequal distribution of wealth and power within the network. This core issue necessitates more rigorous examination and underscores the urgency for remedies that re-establish equilibrium and honour the essential principles of blockchain technology.

Financial Losses#

Certain forms of MEV extraction can result in direct financial losses for users. A case in point is the predatory sandwich attacks, which led to profits exceeding $3 million for attackers in November 2022 alone [Eig22]. This substantial gain was, unfortunately, the result of monetary losses suffered by the victims.

Inefficiencies Stemming from Coordination Deficit#

The competitive pursuit of MEV by bots can lead to on-chain bidding battles. These contests may contribute to network traffic jams and inflate transaction costs. Some strategies intended to counter MEV can unintentionally trigger other forms of inefficiency. For instance, implementing a first-come-first-served transaction ordering can shift the competitive battleground to off-chain latency, thereby instigating off-chain latency wars among MEV searchers.

Threat to Consensus Stability#

Carlsten et al. [CKWN16] demonstrated that when transaction fees surpass block rewards, miners may stray from honest mining practices. They could create forks with high-fee blocks to entice other miners to contribute to their forks. MEV can be seen as an expanded form of transaction fees directed to the miner, and a significant MEV can amplify this issue. Today, lucrative MEV extraction often outweighs block rewards [Fla22].

Daian et al. [DGK+20] detailed an additional attack method that leverages MEV, referred to as Time-bandit attacks. Essentially, this approach enhances the reorganisation of 51% attacks by supplementing them with financial support derived from MEV.

A Catalyst for Centralisation#

Vitalik [But21] asserted that MEV could foster centralisation given the notable economies of scale associated with uncovering complex MEV extraction opportunities. A future dominated by centralisation and monopoly is undesirable as it undermines the principles of transparency and decentralisation. There’s also a concern that MEV could promote “vertical integration” [HG22] where miners and traders combine to establish exclusive systems. This development could potentially jeopardise the transparency and permissionless nature of the blockchain.

Solutions and Future Directions#

MEV Auction Platforms#

MEV auction platforms serve to facilitate auctions that allocate block space to users who place bids for their transaction inclusion. They place a high emphasis on transaction privacy and atomicity. Their services are mostly availed by MEV searchers, who carry out their MEV extraction transactions covertly, and regular users who protect their transactions from being exposed to searchers [YZH+22].

With the Ethereum merge, MEV auction platforms bifurcated into pre-merge and post-merge types. Pre-merge platforms like Flashbots and Eden Network use first-price sealed-bid auctions. Post-merge platforms are set to see native support in the form of a Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS) protocol in future Ethereum versions. However, an interim realisation, MEV-Boost, continues to rely on trusted relays. For users exclusively interested in privacy, these platforms offer private channels that can be accessed via RPC endpoints [YZH+22].

Time-Based Transaction Ordering#

Time-based ordering properties form a category of solutions aimed at preventing transaction order manipulation in the blockchain ecosystem. The concept, initially proposed by Kelkar et al. [KZGJ20], is built around “receive-order fairness,” which is a first-come-first-served approach to transaction ordering. This notion has been further explored and improved upon by systems, which offer enhanced liveness and reduced communication complexity.

In the field of transaction ordering, relative fairness has also been a focus of exploration. Kursawe et al. [Kur20] propose the concept of relative fairness, stipulating that if all honest validators see transaction T before a given time and another transaction T’ after this time, T should be scheduled before T’. Zhang et al. [ZSC+20] offer a similar concept called ordering-linearizability. While there are slight differences in these approaches, they can be integrated into a single property referred to as fair separability.

Baird et al. [Tea20], in their exploration of Hashgraph, introduce a method that assigns each transaction a fair timestamp, derived from the median time that each node reports receiving the transaction first. A potential vulnerability in this method, however, is that a single adversary could manipulate a median-time-based order.

Conclusion#

MEV, while a challenging facet of the blockchain universe, offers valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of blockchain systems. Its study reveals critical areas of vulnerability, while also inspiring new strategies for enhancing system fairness and security. As the blockchain landscape continues to grow and evolve, addressing the issue of MEV will remain a pivotal focus in ongoing academic research and technological innovation.

References#

- But21

Vitalik Buterin. Proposer/block builder separation-friendly fee market designs. Ethereum Research, 2021. URL: https://ethresear.ch/t/proposer-block-builder-separation-friendly-fee-market-designs/9725.

- CKWN16

Miles Carlsten, Harry Kalodner, S Matthew Weinberg, and Arvind Narayanan. On the instability of bitcoin without the block reward. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 154–167. 2016.

- Cha22(1,2)

Yash Kamal Chaturvedi. Mev in defi. Ether World, 2022. URL: https://etherworld.co/2022/04/05/mev-research-report/.

- DGK+20(1,2)

Philip Daian, Steven Goldfeder, Tyler Kell, Yunqi Li, Xueyuan Zhao, Iddo Bentov, Lorenz Breidenbach, and Ari Juels. Flash boys 2.0: frontrunning in decentralized exchanges, miner extractable value, and consensus instability. In 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 910–927. IEEE, 2020.

- Eig22

EigenPhi. Sandwich overview | eigenphi. EigenPhi, 2022. URL: https://eigenphi.io/mev/ethereum/sandwich.

- EMC20

Shayan Eskandari, Seyedehmahsa Moosavi, and Jeremy Clark. Sok: transparent dishonesty: front-running attacks on blockchain. In Financial Cryptography and Data Security: FC 2019 International Workshops, VOTING and WTSC, St. Kitts, St. Kitts and Nevis, February 18–22, 2019, Revised Selected Papers 23, 170–189. Springer, 2020.

- Fla22

Flashbots. Transparency dashboard | flashbots. Flashbots, 2022. URL: https://dashboard.flashbots.net/.

- HG22

Hasu and Stephane Gosselin. Why run mev-boost? Flashbots, 2022. URL: https://writings.flashbots.net/why-run-mevboost/.

- KZGJ20

Mahimna Kelkar, Fan Zhang, Steven Goldfeder, and Ari Juels. Order-fairness for byzantine consensus. In Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2020: 40th Annual International Cryptology Conference, CRYPTO 2020, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 17–21, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 40, 451–480. Springer, 2020.

- Kur20

Klaus Kursawe. Wendy, the good little fairness widget: achieving order fairness for blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies, 25–36. 2020.

- QZG+21

Kaihua Qin, Liyi Zhou, Pablo Gamito, Philipp Jovanovic, and Arthur Gervais. An empirical study of defi liquidations: incentives, risks, and instabilities. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM Internet Measurement Conference, 336–350. 2021.

- Tea20

Hedera Team. Hedera technical insights: fair timestamping and fair ordering of transactions. Hedera, 2020. URL: https://hedera.com/blog/fair-timestamping-and-fair-ordering-of-transactions.

- TYME21

Itay Tsabary, Matan Yechieli, Alex Manuskin, and Ittay Eyal. Mad-htlc: because htlc is crazy-cheap to attack. In 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 1230–1248. IEEE, 2021.

- WHF19

Fredrik Winzer, Benjamin Herd, and Sebastian Faust. Temporary censorship attacks in the presence of rational miners. In 2019 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), 357–366. IEEE, 2019.

- YZH+22(1,2,3)

Sen Yang, Fan Zhang, Ken Huang, Xi Chen, Youwei Yang, and Feng Zhu. Sok: mev countermeasures: theory and practice. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.05111, 2022.

- ZSC+20

Yunhao Zhang, Srinath Setty, Qi Chen, Lidong Zhou, and Lorenzo Alvisi. Byzantine ordered consensus without byzantine oligarchy. In 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), 633–649. 2020.

- ZQT+21

Liyi Zhou, Kaihua Qin, Christof Ferreira Torres, Duc V Le, and Arthur Gervais. High-frequency trading on decentralized on-chain exchanges. In 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 428–445. IEEE, 2021.