Optimising Cross-Chain Swaps: A Game Theoretic Analysis of HTLCs and Packetised Payments#

Academic Insight

Key Insights

The integration of cross-chain interoperability is crucial for a variety of decentralised finance (DeFi) applications such as decentralised exchanges (DEXs) and decentralised applications (DApps). The technology must be trustless to prevent reliance on centralised intermediaries, Hash Time Locked Contracts (HTLCs) are commonly used for this purpose.

Atomic swaps present a risk of asset value fluctuation during the exchange, increasing the likelihood of one party abandoning the swap. This can result in opportunity costs for the other party.

A game theoretic framework can be established to construct a parametrised solution for determining the success rate of cross-chain swaps through HTLCs and Packetised Payments (PPs).

The current parameters often lead to high failure rates in cross-chain swaps. In the context of PPs, these parameters can theoretically enable malicious actors to gain profits.

The game theoretic framework is extended to derive optimisation solutions that enhance the success rate of atomic swaps and PPs, focusing on collateralisation and adjustable exchange rates.

Introduction#

In the Decentralised Finance (DeFi) landscape, interoperability between disparate blockchain networks is paramount for data and value transmission across chains [Mao22]. Cross-chain technology has applications in Decentralised Exchanges (DEXs), cross-platform Decentralised Applications (DApps), tokenised real assets, distributed transaction platforms, etc. The technologies need to enable secure and trustless transactions to prevent reliance on centralised intermediaries. To this end, Hash Time Lock Contracts (HTLCs), a form of atomic swaps, are commonly used to achieve cross-chain asset exchange. HTLCs and all other atomic swaps have inherent risks associated with them: (1) value fluctuation during the exchange, and (2) high incentives for malicious agents [DR23]. An alternative approach is Packetised Payments (PPs) [Rob19], which implement a series of alternating transactions to achieve cross-ledger exchange. This article summarises the recent studies regarding these protocols - unravelling their execution success rate bottlenecks and exploring the proposed solutions [JX21] [AD21].

HTLCs#

HTLCs are a type of smart contract that uses elements of cryptocurrency on-chain transactions along with hash-lock and time-lock contracts to reduce counterparty risk in cross-chain asset exchange [JP16]. A hash lock is a hashed or cryptographically scrambled version of the secret (key) generated by the agent initiating the swap and is used by both agents to lock their assets and exchange them. The swap is complete when the initiating agent reveals the preimage of the hashlock to access the received assets, which enables the second agent to access their received assets. Further, if the HTLC contract is not completed within the pre-determined time constraint, both parties automatically receive their initial assets, and the swap fails.

PPs#

Packetised Payments start by breaking down transactions into packets. Further, on each step, the participant would match the previous transfer and extend their transfer, hence ensuring equal distribution of counterparty risk. If any participant were to exit the transaction, the other agent would lose a maximum of one packet, which is sized to be economically insignificant.

Game Theoretic Analysis#

A game theoretic framework is developed to sequentially analyse events in the two protocols and derive probabilities for the success rate of cross-chain exchanges. The detailed version of the below discussion can be found in [JX21] [AD21].

Game Theoretic Framework for HTLCs#

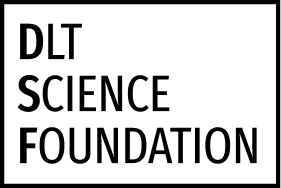

Two agents, Alice (\(A\)) and Bob (\(B\)), are aiming to trade \(token_a\) From \(chain_a\) for \(token_b\) from \(chain_b\) at a defined exchange rate \(P^*\). \(token_b\)’s price at time t is denoted by \(P_t\). At each step during the exchange, the agents can choose to either stop or continue the exchange. The steps are as follows –

Step 1: (\(A\)) decides whether to initiate the swap by writing a swap HTLC on \(chain_a\) (cont) or not (stop).

Step 2: (\(B\)) decides whether to write an HTLC on \(chain_b\) (cont) or not (stop).

Step 3: (\(A\)) decides whether to unlock \(token_b\) (cont) or not (stop).

Step 4: (\(B\)) decides whether to unlock \(token_a\) (cont) or not (stop).

Fig. 1 HTLC game diagram.#

Through backward induction, an optimal strategy is derived for each agent to maximise their utility functions at each step. In step 4, it is trivial to deduce that B continues as \(A\) has already accessed \(token_b\). In step 1 and step 2, \(P_t\) has to be in a viability range for the swap to continue. \(P_t\) being higher than a derived maximum or minimum would bring the success probability to zero.

In step 3, \(A\) gets to make the sole decision of whether to complete the swap or not, hence can choose to stop if the exchange price drops and execute if it rises. In this instant, \(A\) has the optionality akin to an American option, as she can choose to execute or not at any moment up to the expiration time.

It is found that in steps 1 to 3, the greater the range between minimum and maximum viable values of \(P_t\), the higher the probability of the swap succeeding.

Key Findings#

Exchange Rate: The success of the swap depends on a defined range of exchange rates \(P^*\). Deviations from this range significantly impact the success probability. The overall success rate is highly sensitive to the range of values allowed for \(P^*\); therefore, the stability and security of HTLCs can be optimised by maximising this range.

Success premium: This is the measure of how determined each party is to see the swap succeed. Actors with low success premiums would cause a low success rate for the swap and come off as malicious. A high success premium leads to a high success rate and a greater range of feasible \(P^*\).

Time preference (r): Time preference describes an agent’s impatience level - the desire to access assets now rather than later. larger r results in a narrower viable range of values for \(P^*\). If r is greater than a calculated critical value, the swap is rendered impossible as no \(P^*\) remains feasible.

Transaction confirmation time: Higher confirmation time on either chain shrinks the viable range of \(P^*\) as the increased time taken reduces the transaction utility functions for either or both parties. When \(P^*\) is chosen to maximise the success rate, a lower confirmation time increases the success rate.

Price trend and volatility: A High upward trend of the exchange rate increases the success rate as Alice is highly likely to decide in favour of the final optionality she receives. In contrast, higher volatility reduces the success rate.

HTLCs experience reoccurring and numerous transaction failures. Hence, it can be stated that existing parameters and success premiums of agents are stacked such that success rates cannot be optimal.

Extending the above game theoretic framework to PPs proves that not only do malicious agents have no incentive to complete transactions, but also that they can enter multiple transactions in parallel to generate large profits.

Optimising Cross-Chain Swaps#

This game theoretic analysis is persistent across various trustless cross-chain swap protocols [MB20]. Therefore, solutions derived by extending the methodology can be widely implemented to generate higher success rates of swaps and minimise incentives for malicious actors to stop the exchange.

Swaps with collateral#

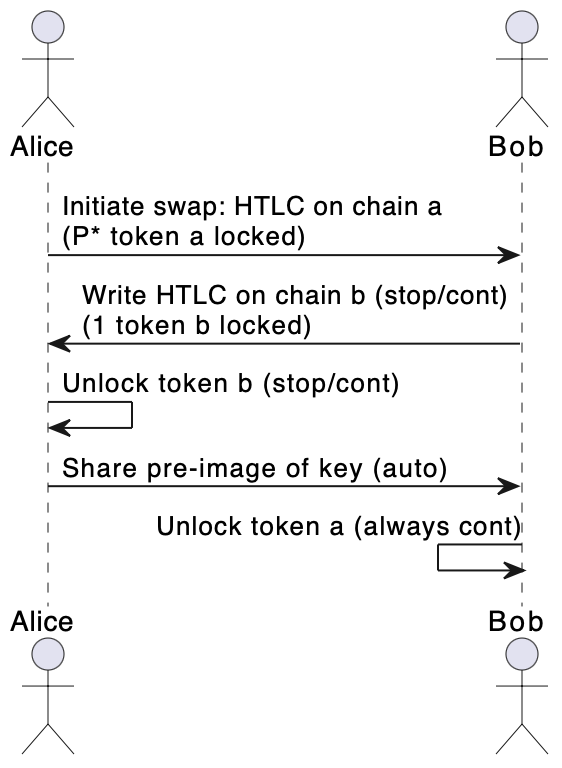

Alice and Bob move an allowance to a trusted smart contract on \(chain_a\) to charge each of them simultaneously the same amount of collateral, \(Q\) \(token_a\), before the swap. The smart contract can be connected to an oracle that observes the transaction. If any agent decides to stop at any time, the other agent receives both collaterals.

Fig. 2 HTLC with collateral game diagram.#

The extension of the game theoretic framework to this system shows that the success rate increases with collateral amount \(Q\). This is because higher \(Q\) allows for larger exchange rate \(P_t\) movements; consequently, the sensitivity of the success rate towards \(P^*\), volatility, and trend is reduced. The incentives that malicious actors may gain from massive price movements are eliminated by the loss of higher collateral. Therefore, the best strategy for malicious actors is to continue – maximising the success rate of the swap.

Adjustable Exchange Rates#

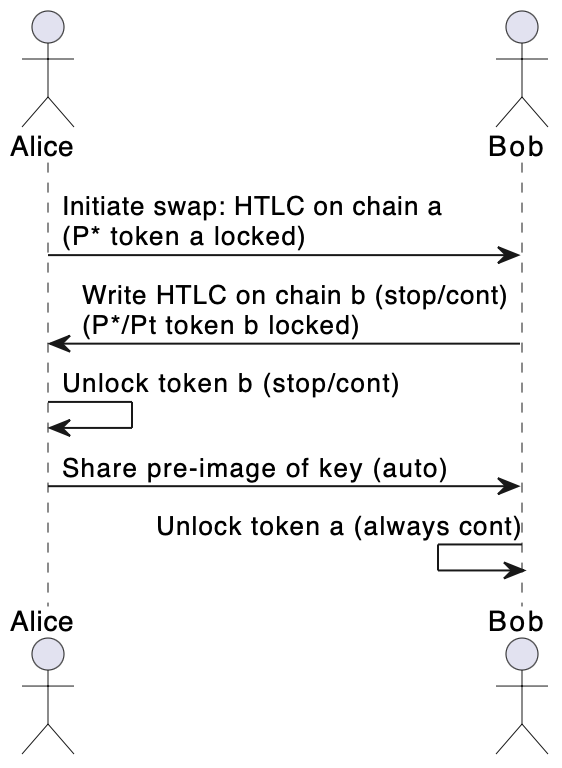

This is an extension to the HTLC game. The agents not only have the freedom to choose to continue or stop, but they can also decide the exact amount of funds to lock in, that is, \(P^*\) isn’t fixed and can be adjusted as \(P_t\) changes on each step.

Fig. 3 HTLC with adjustable exchange rate game diagram.#

It is found that the absence of a pre-determined exchange rate boosts the success rate and allows for the possibility of success over a wider range of exchange parameters.

Conclusion#

The game theoretic approach developed in the referenced papers and discussed above is a rigorous quantitative method to study the viability and sensitivity of various cross-chain technologies. An analysis of HTLCs and PPs reveals execution success rate bottlenecks. The findings are not local to these protocols as other investigations successfully apply similar game theoretic analysis to a variety of protocols. Extending the analysis offers crucial solutions - collateralisation and adjustable exchange rates. These help mitigate counterparty risks by aligning incentives for all parties. The findings, applicable across various trustless cross-chain swap protocols, offer a blueprint for elevating success rates and minimising vulnerabilities, contributing to the advancement of secure and efficient decentralised finance ecosystems.

References#

- AD21(1,2)

Jiahua Xu Alevtina Dubovitskaya, Damien Ackerer. A game-theoretic analysis of cross-ledger swaps with packetized payments. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2021. URL: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-662-63958-0.pdf.

- DR23

Tien Tuan Anh Dinh Daniël Reijsbergen, Bretislav Hajek. Crocodai: a stablecoin for cross-chain commerce. 2023. URL: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.09754, arXiv:2306.09754.

- DMHM19

Dr David Donald Dr Mahdi H. Miraz. Atomic cross-chain swaps: development, trajectory and potential of non-monetary digital token swap facilities. SSRN Electronic journal, 2019. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330419487_Atomic_Cross-Chain_Swaps_Development_Trajectory_and_Potential_of_Non-Monetary_Digital_Token_Swap_Facilities.

- JX21(1,2)

Alevtina Dubovitskaya Jiahua Xu, Damien Ackerer. A game-theoretic analysis of cross-chain atomic swaps with htlcs. IEEE, 2021. URL: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDCS51616.2021.00062.

- JP16

Thaddeus Dryja Joseph Poon. The bitcoin lightning network: scalable off-chain instant pay- ments. Lightning Network, 2016. URL: https://lightning.network/lightning-network-paper.pdf.

- Mao22

Hanyu Mao. A survey on cross-chain technology: challanges, development, and prospect. IEEE Access, 2022. URL: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=9982450&tag=1.

- MB20

Maria Potop-Butucaru Marianna Belotti, Stefano Moretti. Game theoretical analysis of cross-chain swaps. IEEE, 2020. URL: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9355687.

- Rob19

D Robinson. Htlcs considered harmful. Stanford Blockchain Conference (2019), 2019. URL: http://diyhpl.us/wiki/transcripts/stanford-blockchain-conference/2019/htlcs-considered-harmful/.